Three Guilt-Free Tips for Weeding the Library

Join Our Community

Access this resource now. Get up to three resources every month for free.

Choose from thousands of articles, lessons, guides, videos, and printables.

Our school and classroom libraries should ignite ideas, fill us with knowledge, and inspire a love of reading. Students should be able to access relevant information when they need it, as well as books and authors they love so they can get lost in books that will make them lifelong readers.

One key to maintaining a high-quality classroom library is something called weeding. Weeding is simply the process of culling old, outdated, damaged books and reading material to make room for the new. This process also makes what is already in the collection easier to find. Some of you may have just gasped. If you feel like books are sacred and you couldn’t possibly part with any of them, we encourage you to read on.

If you have 700 books in your library, but only 500 of them are appealing to students, then the extra titles aren’t doing anyone any good. In fact, they are a burden for students to wade through when looking for the perfect good-fit book. We can gain a tremendous sense of freedom if we remember that the purpose of a classroom library is not to archive and preserve every piece of reading material that has come through the doors (leave that to the Library of Congress); instead, our goal is to maintain a vibrant, healthy library.

If you are ready to look at your library with a critical eye toward what should stay and what should go, here are three things to consider.

- Is it in good shape?

Books with excessive wear and that are in disrepair are unlikely to be chosen. If they can't be mended and restored, they can go. - Is the information accurate?

We don’t want our students to have to guess which books they can count on for reliable information. Nonfiction books that are over three years old might already be out of date. Students who rely on them might be misled in harmless ways (including Pluto as a major planet of our solar system), or in harmful ways (shark cartilage can be used to cure cancer, and tapeworms can help us lose weight). Books with out-of-date information can and should be culled from our collections, and we can eliminate them guilt-free. - Is it a classic or out of date?

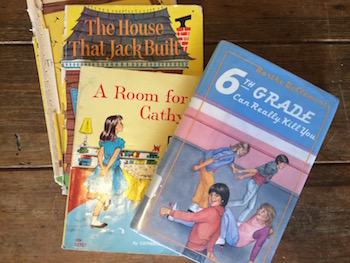

Students may still love Put Me in the Zoo by Robert Lopshire, and Charlotte’s Web by E. B. White, but other books may be clunkers instead of classics. Take for example this opening from 6th Grade Can Really Kill You by Barthe DeClements, which has cultural references from 1985 that will leave today’s students scratching their heads:

“Oh, Helen,” my mother complained, “you’re not going to wear those denim pants the first day of school are you?”

Oh my. So funny. It gets better (or worse) when the mother tells her to brush her hair a certain way to look a little more like Liza Minnelli, a suggestion Helen regards with disdain before grabbing her Pee Chee and heading off to school. (Her Pee Chee! I colored on those when I was bored in class back in 1975! Many of you aren't even going to know what they are, so I've included a photo.)

Seriously, we can eliminate books like that without even a pang of guilt. In fact, I weeded it from the K-6 school library when I was a full-time librarian. Let's keep the classics that kids still love, and remove the titles that are no longer culturally relevant.

Whether maintaining a school, classroom, or home library, culling the shelves is an important process if we want the library to engage our children.

Want more? Check out this great poster. Jennifer LaGarde uses the acronym FRESH to keep her library vibrant and alive. Her criteria for what stays and what goes is perfect for our libraries, too.